My childhood in Southern California could be described as a very Asian American experience. Korean restaurants and grocery stores played a variety of Korean music (with only the truly hip restaurants playing K-pop). Everyone I knew watched some combination of anime and dramas. I ate shrimp chips and Melon Bars as snacks and had a distant awareness of the “other” America’s treats. Just like growing up in any culture, of course I had some sad experiences but I was happy with what I had.

Back then, my conversations with non-Asian Americans would often have the question of ‘Are you Chinese or Japanese?’ not because of racism, but out of ignorance. I would think to myself “There’s also South Korea!” but at that time, North Korea was its more infamous sibling since it was designated as part of the “Axis of Evil”. I’m sure every Korean American who grew up in the late 90s and 00s swore to themselves “One day, [South] Korea will be known.”

That was a curse however.

As a child, I didn’t understand the conditions and ideals behind the anime and mangas I enjoyed and loved. I watched Princess Tutu, Revolutionary Girl Utena, and Sailor Moon while also actively consuming from the Shonen Jump catalog of that time (think Bleach, One Piece, and Naruto along with its lesser counterparts of Katekyo Hitman Reborn counterparts). It’s not that I didn’t understand the themes and stories, but I didn’t realize that there were many social and political currents behind the creation and publication of these comics and shows I loved so much. Around the time I started university, I found myself less and less interested in anime and manga. I thought it was mostly because I was growing up, but I also had some mild distaste for the “Attack on Titan”-ification of the medium.

“Attack on Titan” was very popular during my university years and I was generally aware of its fascist and imperialist themes and its war apologist author. I read some of it, but I ended up dropping it early on when I found out about the author’s beliefs. I also found the death for death’s sake narrative trite, making it an easy drop. I grew more and more distant from the medium as the anime became more and more popular. I would dip my toes in occasionally and try reading through some titles like ‘My Hero Academia’ but I never committed like I did in my childhood because I found the stories dull and the characters lacking. During the same time, I was also growing some historical awareness of what it meant to be Korean and the popularity of ‘Attack on Titan’ had confirmed to my uncharitable mind that Japan would always be like that - unapologetic of its fascism.

I stopped consuming Korean pop culture as well. When I went to university, I found myself hopelessly ignorant of the ‘other’ America’s shows and movies and wanted to fix that. It also helped that American music began to drag itself out of the ‘Imagine Dragons’ mire of the early 2010s. Because of this, I found the shift from second-generation K-pop to the third and fourth generation more jarring than it should have been when I finally came back “home”.

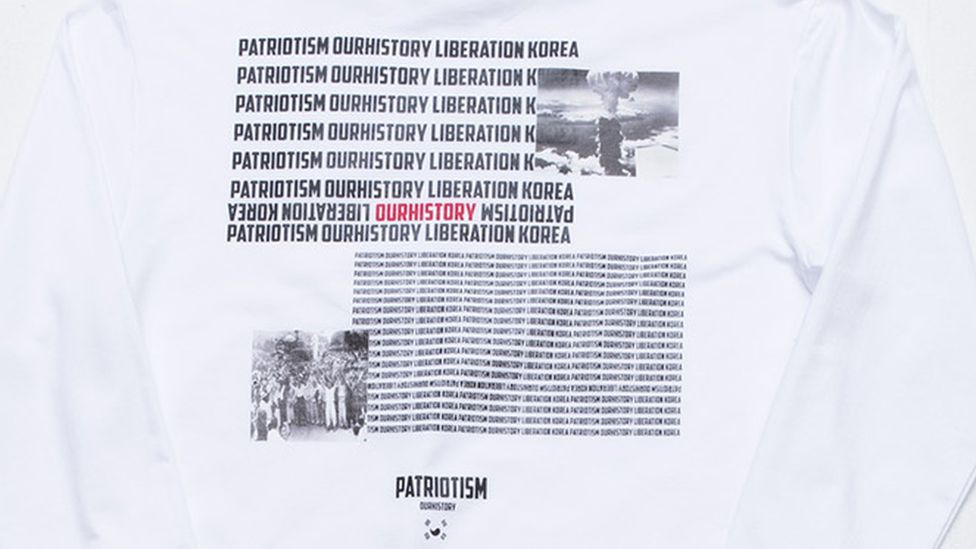

When I found out that BTS was extremely popular in late 2017 through my friends who were fans of them, I just wondered ‘Aren’t they incels? Isn’t their music mediocre? Don’t they draw in stupid people? to myself’, but dismissed it thinking that I just had hater tendencies. I didn’t pay much attention to them until a Japanese radio station canceled their appearance over one of their members wearing a shirt depicting the atomic bombing of Japan (see image below).

My family had made personal sacrifices for a free and independent Korea and that pride was instilled in me from an early age, but I found something about that shirt off-putting. I was aware that the atomic bombings were not necessary to force Japan’s surrender and gain Korea’s liberation. I found it cruel of the United States to test out these atomic weapons on civilian populations that held many enslaved Koreans there as well. There were so many other images and depictions of Korean liberation; why was a cruel American action associated with Korean liberation and nationalism? I added this moment to my mental list of why I disliked BTS and moved on, still thinking this moment was an outlier.

I’ve always kept tabs on Korean politics and had an understanding of the circumstances around Park Geun Hye’s election. In late 2019, South Korea had its midterm elections and I found the survey results on the growing anti-feminism amongst young Korean men my age disturbing. Close to 80% of Korean men opposed feminism, according to a December 2018 poll, and that number grew worse. Anti-feminism and anti-communism joined hands to fight against the socially progressive policies of Moon Jae-In’s government. At that time, I still believed that this would stay an internal issue and that the squeaky image of Korean pop culture would keep this political polarization away from ignorant fans.

I was wrong however.

In July 2020, Yuta, a member of the boy group NCT, mentioned that he was a fan of Rhee-kun, a right-wing and anti-feminist Youtuber, during an interview and was met with backlash. I was dimly aware that this large demographic of anti-feminists would also include some K-pop idols and young actors; however, I was overly optimistic. Fans defended this revelation of his actual political beliefs and I was left with a growing dread that these right wing viewpoints held by a sizable amount of K-pop idols would be defended by outsiders. This was later confirmed by how K-pop fans defended Snowdrop, a right wing revisionist K-drama, because a member of Blackpink was portraying the main character in late 2021. There are K-pop idols with progressive politics and ideals - Sulli, Sunmi, Jonghyun, Psy (I personally wouldn’t classify Psy as an idol though), and others. It seemed to me that the newer crop of idols leaned more and more conservative despite the liberalism of their “older siblings”.

I asked myself “How could this happen?” and it truly felt as if the heart of my beloved country had something rotten. I then remembered Japan. Despite the growing popularity of anime and manga abroad during the past twenty years, I found it strange how its increased profitability only led to more overworked and underpaid animators, more dull and trite narratives, and more expressed right-wing sentiments. I now understand that the growing international demand desired the beautiful battle scenes and sex appeal without sexuality. Right wing narratives could provide this on a shoestring budget while minimizing creativity and complexity.

I had complained that anime and manga weren’t the same anymore, and then much later, complained that the Korean Wave ruined Korean media (and food).The international hyper-consumption of Korean culture is loading it onto the same right-wing train as anime and manga boarded a decade ago. The future of the Korean Wave appears to be much worse since it encompasses movies, webcomics, TV shows, and music while most of Japan’s pop culture survived the acidity of the world’s stomach. As South Korea grows more polarized and this anti-feminist, anti-communist, and Sinophobic ideology grows more powerful, portions of the Korean Wave will also support and express this ideology. The fans have supported this right-wing ideology and will continue to, just as anime and manga fans did before because they have no ideology outside of consumption.

It is easy to despair as the world’s consumption engine continues to demand more and more cheap and low-quality media that feeds into fascism with its empty narratives and militaristic themes. I still have hope. In Japan, the latest installment of the Yakuza video game series defended the complexity of the “gray zones” with a cast of morally-complex and diverse characters. The Japanese movie ‘Drive My Car’ has a complex narrative, but its story and themes are executed well by its diverse cast. There are still so many in Korea and Japan who have so much to say. We just need to look for it.